Lost in Memorialization? (March 2006)

With the Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko’s visit to the Philippines scheduled in late this month, let me share a slightly modified version of the paper I presented in March 2006 at the symposium commemorating the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Philippines-Japan diplomatic relations. While the paper discussed the situation as of March 2006, I’ve found it is worth repeating/sharing the argument I made the decade ago in the face of present circumstances.

Lost in Memorialization?

–Unmaking of ‘History Issues’ in Postwar Philippines-Japan Relations–

Paper presented at the Symposium: The Philippines-Japan Relationship in an Evolving

Paradigm, March 8-9, 2006 at the Don Enrique Yuchengco Hall, De La Salle University,

Taft Avenue, Manila (organized by JICC Embassy of Japan, Japan Foundation, Manila,

and Yuchengco Center, DLSU)

Last modified for web publication: 17 January 2016

—— More —–

Lost in Memorialization?

–The Unmaking of “Historical Issues” in Postwar Philippine-Japanese Relations–

(Transcript for the proceedings)

Satoshi Nakano

Introduction

In this paper I would like to discuss (1) the pattern which might be called a “virtuous circle of Japanese apology and Filipino forgiveness” that has transformed the postwar Philippine-Japan relations from one of hatred to reconciliation; (2) the historical significance of the war dead memorialization as an important factor in the making of that “virtuous circle”; (3) “lost in memorialization” or fading war memories (on the Japan’s side) as the flip side to reconciliation, which potentially could have dangerous consequences in relations between the two countries; (4) the signs of discontent expressed by the Philippine media concerning the lack of publicity in the recent years about Japanese wartime atrocities and wrongdoings in the Philippines; success of the “preventive diplomacy” strategy adopted by the Japanese Embassy from 2005 to 2006; and (5) what more should be done in terms of the possibility of sharing and preserving war memories between the two nations without provoking any antagonism. In sum, I would like to point out that we have to go beyond what has been achieved by official diplomacy in order to realize a more desirable and much deeper level of reconciliation between the Philippines and Japan.

1. The “Virtuous Circle” of Apology and Forgiveness

There has been established a pattern between Japan and the Philippines since the 1980s at the latest, in which Japanese apology and Filipino forgiveness characterized the mood and created the “virtuous circle” between the two countries. This stands in stark contrast to the Northeastern Asian “historical issue” disputes, which have been characterized by a “vicious circle” of harsh exchanges of words and provocations.

For example, when Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone visited the Philippines in May 1983, he was so moved by the welcoming crowds (apparently mobilized by the then dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos) that he personally redrafted a banquet speech, in which he went as far as to say, “our country deeply regrets and repents having caused your country and people such trouble in the past war. The more you treat us with warm friendliness and generosity, the deeper should we repent and castigate ourselves.” This was the first time on any occasion that Nakasone had ever expressed “repentance for the past” in such clear terms.[1] Also noteworthy was President Corazon Aquino’s state visit to Japan in November 1986, when Emperor Hirohito allegedly “kept apologizing for what Japanese caused the Philippines,” while Aquino told the Emperor “to forget about this.”[2] The successful handling of “comfort women” issues in the Philippine-Japan relations might also be included as another case in point.

Such is the pattern that has been established between the two governments, in which the Japanese side would make an apology and the Philippine side would accept it in good faith. This has not been the case with China or Korea since the 1980s. The contrast becomes even more remarkable when we consider the fact that the Philippine government was once almost alone in challenging the western democracies about Japan’s return to the international community during the early postwar years, expressing skepticism about the truthfulness of Japanese determination to eliminate militarism,[3] while Filipinos as a people were regarded as harboring the worst “feelings against Japan (tainichi kanjo)” for many years after the war because of their intolerable experiences during the war.

The transformation of the bilateral relations from one of hatred to tolerance, and then to forgiveness, was brought about by a combination of several factors, including international politics of the Cold War, war reparations, ODA, trade and investment, and so forth. However, in my previous article titled “The Politics of Mourning,”[4] I stressed the significance of an accumulation of positive images generated from increased contact between the two nations in memorializing the war dead as the socio-cultural basis of the transformation. Let me summarize my argument.

2. The Significance of War Dead Memorialization

Because of the vast number of Japanese who died in the Philippines during the Asia-Pacific War, some 518,000,[5] memorialization practices, including collecting war dead remains (bone gathering), pilgrimage tours by bereaved families and veterans, as well as erecting statues and markers, were more widely held in the Philippines than any other countries out of Japan. Japanese government missions for gathering remains have been sent to the Philippines since 1958, while pilgrimage tours organized by the Japanese War Bereaved Association (Nippoin Izokukai; JWBA), prefecture governments, and various tour agencies have been sent to the Philippines since the mid 1960s. The peak was reached in the year 1977, declared by President Marcos as the “Year of Peace,” to attract the war bereaved and veterans from all the countries concerned: Japan, the United States, Australia, etc., to the Philippines in hope of promoting tourism. The number of pilgrimage tours declined after the 1980s due to both political chaos in the Philippines and the advancing age of Japanese bereaved families and veterans. However, many Japanese in their 80s or even 90s continue to visit the Philippines to memorialize their war dead to this date.

What is important is not the number of pilgrims but the patterns of behavior and experience exemplified by the Japanese government missions and pilgrimages, which can be gathered from government reports, numerous private publications, local newspapers, as well as the journal of the JWBA and other organizations which sent tours to the Philippines since the mid-1960s. What I concluded can be summarized as follows,

(1) Knowing or having been informed that the country they would visit to memorialize their war dead had been devastated by Japan, pilgrims tend to be more sensitive to the Filipino sense of victimization than the average Japanese. Quite often they felt that they had to apologize for Japanese misdeeds in the war. Their apologies, however, were usually made only in general terms and rarely did they admit their own lost loved-ones’ or lost comrades’ wrongdoings. In many cases they tend to think that ceremonies should be held in a spirit of “joint memorialization” commemorating the war dead of both nations (in some cases all the nations concerned including Americans, Australians, etc.).

(2) Those Filipinos who received Japanese missions and pilgrim tourists, assuming that they (Japanese) knew their (Filipino) sufferings, tend to display hospitality by not taking grudges or avoiding any “collision of memories,” showing tolerance and generosity to the mourning visitors.

(3) The average reaction of Japanese pilgrim visitors towards such Filipino generosity, which not only allowed but even welcomed the former enemy to come and memorialize their war dead, was one of deep gratitude. Many visitors thus became “repeaters,” and many of them came to think of the Philippines as a more appropriate place to preserve their memories of loved-ones or comrades than Japan, even as “a second home”.

(4) There seems to have existed a kind of reciprocity between the kindness shown by Filipinos and Japanese contribution to the local communities (or ODA on the national level), although such cases as “trade” in human bones as well as arrogant attitudes taken by some of the veteran tourists and bone gathering missions show the relation between the pilgrim tourists and their hosts did not always deserve such reciprocity. On the other hand, positive efforts to maintain reciprocity in many cases developed into important grassroots non governmental civic exchanges between the two nations. I also pointed out that the largest bereaved family association, JWBA, shared much of the above-mentioned experiences in their very satisfactory relations with the Philippines, which was well summarized in Tadashi Itagaki’s address at the 1977 memorial ceremony held in Carilaya Memorial Park.

“sincerity and truthfulness of the war bereaved families has opened a way to heart-to-heart exchange between our two nation, transcending love and hate and leading to the establishment of amicable relationships due to the efforts of people in the both countries. This is ample proof of the fact that those who died heroically in battle on both sides will live forever as the foundations of peace.” [6]

This kind of satisfaction expressed by one of the top JWBA officials had a very important political implication, since many self-acclaimed nationalist politicians in the Japanese Diet have more or less relied on the support of the organization in their election bids. It is my assumption that the JWBA’s friendship with the Philippines is not unrelated to the total absence of negative remarks, or “gaffe,” from the Japanese right-wing nationalist politicians, while those same politicians are very likely to show strong resentment concerning the Japanese “diplomacy of apology” towards China and Korea. The absence of “gaffe” is significant because it has made the Philippine-Japan diplomatic relations as well as the public sentiments in the both countries much less strained than the situation in China and Korea.

3. Reconciliation and Fading War Memories

In terms of Japanese diplomatic history, the Philippines-Japan postwar reconciliation coupled with the war dead memorialization is a remarkable success story of establishing a forward-looking bilateral relationship that the Japanese government has so desired with all its Asian neighbors.

There is, however, a flip side to reconciliation through memorialization.

To begin with, memorializing war dead is different from recalling or preserving war memories.

Just imagine attending a funeral or any other memorial gathering like one commemorating the September 11th attack held in lower Manhattan. When mourners gather, they assume everyone knows what happened to the victims, who quite often died in unspeakable misery and horror, especially in time of war. People therefore tend to deem it not only unnecessary, but even undesirable, to recall the graphic circumstances of the tragedy surrounding the dead. In this sense, amnesia could be desirable not only for Japanese but Filipino mourners as well, since neither can really recover fully from their loss of loved-ones and traumatic wartime experiences. How long did it take for Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, an important Filipina intellectual, or Vicky Quirino, President Elpidio Quirino’s daughter, to speak out about their near-total loss of family and all the traumatic experiences suffered during the Battle for Manila? And the war was equally traumatic for the Japanese as well, something about which we ask our fathers and mothers and are greeted with a long uncomfortable pause before receiving any reply.

It is in this way that Japanese war dead memorialization in the Philippines, accompanied by host-Filipino desires to avoid bringing up past traumatic memories, has worked not so much to preserve war memories, but rather to quicken their erasure. History has rarely seen such a large number of people going overseas to former battlegrounds specifically in order to memorialize their war dead in such continuity for more than four decades. However, it seems that Japanese public memories about the war in the Philippines are finally wearing thin to the point of near-total amnesia at present, especially among younger generation. Not only the undergraduate Japanese students we teach today but even most journalists in the country’s major news media are totally ignorant of the war in the Philippines, even if they are relatively familiar with the history of Japanese colonialism in Korea or the wartime atrocities in China due to clamor of “historial issue” disputes among the three East Asian neighbors.

Over the short term, suppressing ugly memories and encouraging both parties to forget them might well have promoted a relaxation of tension and creation of mutual amity. In the long run, however, the erasure of war memories may result in unsettling bases of mutual understanding about the past. This rather dangerous aspect of “war amnesia” first became evident (in my opinion) between 1994 and 1995, when a series of the 50th anniversary events celebrating the liberation of the Philippines aroused among the Filipino population memories of the war and Japanese atrocities, while the Japanese news media completely failed to cover the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Manila and the Filipino victimhood in the war.

After 10 years has passed now, there is no doubt that Japanese amnesia about the Battle of the Philippines has reached a point of total erasure of any public memories about that event. Recent developments (2005-2006), in which the Embassy of Japan responded very successfully, show how this loss of memory could have potentially dangerous consequences for Philippine-Japanese relations if left untreated.

4. Preventive Diplomacy 2005-2006

Though the Philippine government has long detached themselves from any of the current “historial issue” disputes, whether it be Prime Ministers’ visits to the Yasukuni Shrine or criticism of growing Japanese amnesia and/or insensitivity about the wartime atrocities and wrongdoings they committed,[7] there were signs of discontent, possibly representing seeds of conflict, which appeared in the Philippine news media on the occasions of the 60th anniversary war commemoration events, particularly the one that concerned the Battle of Manila held in February 2005.

There seems to be at least three interrelated factors behind the discontent: (1) the Philippine government’s inattention, or even negligence, about commemorating the Battle of Manila; (2) lack of attention in the international community concerning the Japanese wartime atrocities in the Philippines and (3) a recent Japanese lack of attention and sensitivity to Filipino feelings about their traumatic war memories.

For example, Maria Isabel Ongpin in her February 2005 column lamented that the memorial gathering organized by the Memorare Manila 1945 had not been attended by any Philippine government officials nor congressmen, but only by the diplomatic corps from the United States and EU. Ongpin then stressed the importance of remembrance and thoughtful reflection on the past as a part of a “universal awakening that has risen all over the world affected by World War II.”[8] Concerns about a lack of publicity about the Philippine wartime ordeal both in the international community and among the younger generations of the Filipinos were widely shared by the country’s major newspapers, which carried series of feature articles remembering the Japanese atrocities and U.S. fire, be it friendly or unfriendly, which destroyed Manila as well as other parts of the Philippines during the last months of the war.

Although it should be noted that these columns and feature articles rarely aimed at rousing antagonism, and actually showed remarkable objectivity and tolerance, they nevertheless should be taken as signs of gathering clouds which could develop into a storm if not properly addressed. In February 2005, the Manila Bulletin published a letter to the editor from one person who had been orphaned by the Battle of Manila, protesting the celebration of Philippine-Japanese Friendship Month during February.[9]

Along with other major newspaper columnists, Bambi L. Harper in her November 2005 opinion article had harsh words for the Japanese government, claiming that their had been no official apologies regarding the past invasion of the Filipinos and other Southeast Asian nations. [10] While such an assertion is in fact incorrect, it nevertheless represents a kind of displeasure shared by the Filipino intellectuals and journalists about a lack of Japanese attention to the Philippines whenever the former refers to its past aggression, as opposed to the Yasukuni shrine controversy with China and Korea being continuously spotlighted as the only two critics of Japanese war amnesia.

Feeling a gathering storm on the horizon, I was about to publish an article which would include the following passage: “If I were a Japanese diplomat, I would have sent warning messages to MOFA in Tokyo.” It was in late October 2005 that I was able to withdraw that sentence from the final proof of the article, after having read the text of Ambassador Ryuichi Yamazaki’s message on the occasion of the 61st anniversary of the Leyte landing in the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

“As I stand on this shore, I am moved by a deep sense of remorse and reflections over the tragic fate of all those who have fought to defend this country against the atrocities of Japanese military aggression.” [11]

I am not, sure but I wonder if such words as “atrocities of Japanese military aggression” have ever been uttered by any other Japanese diplomats who has served in the Philippines.

Then I also found that Bambi L. Harper might possibly have been approached and informed by the Embassy of Japan about the Japanese government’s official position regarding its past aggression, for in one of her later columns discussing a brighter side of the Philippine-Japanese postwar relations, she referred to both the Prime Minister Koizumi’s and Ambassador Ryuichiro Yamazaki’s remarks on different occasions of the 60th anniversary of the end of the war, which equally acknowledged, in Harper’s words, “the misery brought about by Japan’s colonial rule and aggression on the people of Southeast Asia.”[12]

Then February came with Memorare Manila 1945 and the very first attendance at that event by a Japanese ambassador, which made the 61st anniversary of the Battle seem much more significant one than the last one. There, Ambassador Yamazaki took the opportunity to make the following statement:

With this historical fact in mind, I would like to express my heartfelt apologies and deep sense of remorse over the tragic fate of Manila. Let me also reiterate the Japanese Government’s determination not to allow the lessons of that horrible World War II to erode, and to contribute to the peace and prosperity of the world without ever waging a war. Last year I participated in virtually all the ceremonies commemorating the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II. In practically all cases, I was invited to lay a wreath and state my remarks, quite similar to today’s ceremony. All of this has led me to be impressed by the noble spirit of reconciliation and the sense of fairness on the part of the Filipino people, firstly, in appreciating Japan as we are now, a nation sharing the values of democracy, freedom and respect for basic human rights, and, secondly, for taking a future-oriented attitude with a view to deepening the friendly relations between our two nations.[13]

One of the participants at the gathering, Bambi Harper, offered the following observation.

THE SILENCE WAS PALPABLE AT PLAZUELA DE Sta. Isabel last Saturday in Intramuros when Japanese Ambassador Ryuichiro Yamazaki…expressed his apologies and deep sense of remorse over the tragic fate of Manila…

There was hardly a dry eye in the audience when Ambassador Juan Rocha, who lost his mother in that holocaust, remarked that it had been difficult to forgive when there was no contrition. Yamazaki’s sincere regrets may go a long way in healing those festering wounds.[14]

Without going into detail about the Ambassador’s wording of his speeches and other factors present in Japanese diplomatic responses to signs of rising discontent in Filipino public opinion on “historical issues,” I would only like to comment that the recent efforts of the Embassy of Japan in the Philippines is a good example of preventive diplomacy, which in this case has been successful in keeping the Philippine-Japanese relations from following the path of the “vicious” circle of “history issue,” which has disturbingly put Northeast Asian international relations of the new millennium in harm’s way.

5. Conclusion: What more should be done?

However successful such preventive diplomacy efforts have been, they, after all, only amounted to symptomatic treatments, which could never cure the root cause of the problem; that is, Japan’s war amnesia. Here it should be noted that neither the recent commendable efforts of Ambassador Yamazaki nor Japanese official apologies repeatedly made in public to the Filipino people, including Prime Minister Nakasone’s statement in 1983 and Emperor Hirohito’s alleged act of contrition in 1986, have ever been given publicity in Japan. This lack of publicity has deprived the Japanese public of any opportunities to learn what happened in the Philippines during the war.

If this absence of memories has resulted from years of Filipino forgiveness, it is to be regretted. It may sometimes be more desirable in search for the international mutual understanding not to avoid but rather continue to recall unpleasant memories of an ugly past. One may also ask what will happen when the era of war dead memorialization finally comes to an end with a change in generation and the two peoples have to confront each other without sharing common grounds or any accumulation of dialogue about their collective past. And the day is coming. What is necessary, then, is to go beyond preventive diplomacy, which is commendable but not enough.

Let me suggest the following in this respect.

(1) Joint historical studies, which are always on the list of solutions to “historical issue” disputes between Japan and China/Korea, can be and should be “revived” between the Philippines and Japan. I use the term “revive,” because there was joint research before. This time “we/we-inclusive/tayo” should tackle such untouched issues as the Battle of Manila and other atrocities, which I believe “we” can, by taking advantage of our accumulation of past collaborations as well as the absence of public antagonism between the two peoples.

(2) Public support and encouragement for memorial and reconciliation projects by such civic groups as Memorare Manila 1945 and Bridge for Peace, a Japanese NPO promoting dialogue between Japanese veterans and the Filipino people. In this respect, Japan-UK reconciliation projects may be regarded a one good precedent. It is also necessary to include at least the United States in these research and reconciliation projects. It was, after all, the conflict between Japan and the United States which “we” fought in the Philippines.

(3) Focus should be put on educating the Japanese public. We (Japanese) should be able to show that Ambassador Yamazaki’s “heartfelt apologies and deep sense of remorse” is shared among the Japanese general public, which, I regret, is far from the case at present. My conclusion therefore is that it may be not so much a silent respect for the dead as a talkative recounting of the past that will be desirable when we think about the future.

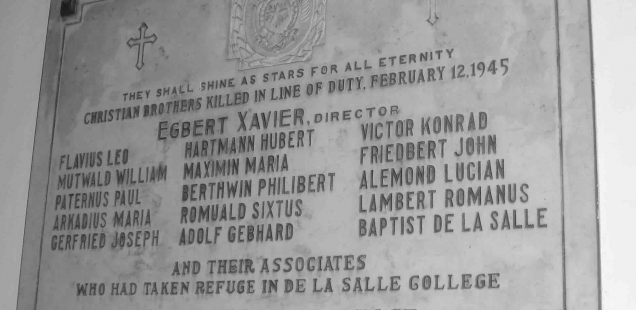

Let me conclude my presentation by remembering the victims of the massacre by Japanese soldiers which took place on this very campus of De La Salle during the Battle of Manila, especially on 12 February 1945, killing most of those women and children, brothers and priests who took shelter here at the time. I hope that the victims, including the then President of the College Egbert Xavier, would rest easier in their graves if we keep on speaking together time and again about their unspeakable deaths.

[1] Asahi Shimbun, 5 May 1983, morning edition, p.1.

[2] Washington Post, November 11, 1986, p. A23.

[3] The most notable example was Carlos P. Romulo’s speech at the Japanese Peace Treaty Conference in San Francisco. See “Excerpts of Speeches Delivered by Delegates at the Japanese Peace Treaty Conference,” New York Times, 8 September 1951.

[4] In Setsuho Ikehata & Lydina N. Yu-Jose, eds., Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo de Manial University Press, 2003, pp.337-376.

[5] The figure is a second only to the 711,000 who were killed in China (including 245,400 in Manchuria). Koseisho Shakai Engo Kyoku [MHW Bureau of Social Welfare and War Victim’s Relief Bureau], ed., Engo 50 nenshi [Fifty Years of War Victim Relief], pp.578-579.

[6] JWBA Journal, No.313, February 1977.

[7] The Philippine Ambassador to Japan Domingo Siazon in an interview article stated that “perceptions of history” had never become an issue between the two counties at the government level.” Asahi Shimbun, 5 September 2001, p.2.

[8] Maria Isabel Ongpin, “Ambient Voices,” Today, 19 February 2005.

[9] “ Not in February! – IF memory serves, it was in February 1986, during the first…” Manila Bulletin, 22 February 2005.

[10] Bambi L. Harper, “Resentments,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 8 November 2005.

[11] “JAPANESE ENVOY EXPRESSES REMORSE OVER WW II,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 21 October 2005, Section 7.

[12] Bambi L. Harper, “That Time of Year,” Ibid. 25 January 2006.

[13] Remarks by H.E. Ambassador Ryuichiro Yamazaki on the occasion of the 61st Anniversary of the Battle for the Liberation of Manila Plazuela de Santa Isabel, Intramuros, Manila, 18 February 2006.

[14] Bambi L. Harper, “Closure,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 21 February 2006.

Recent Comments